SLO testing hits Mayfield, students adapt

November 16, 2014

Following the latest state education legislature, Student Learning Objectives tests are about to become an integral part of Mayfield. But what does that mean?

Essentially, the benchmark tests will be used as progress markers. A test will be taken at the beginning and the end of the year in each class, and the results from each will be used to determine how much students have progressed.

According to Vicky Loncar, the Curriculum Coordinator for Mayfield City Schools, Student Learning Objectives (or SLO tests) “[are designed] to show student growth, [and] to see if we’re showing the level of growth in students that we should be-that the state believes is important for students.”

Students must score “50% of the available growth,” said Loncar. “So if a student scored a 90 percent on the preset, they would only have to score a 95% to meet the [state] goals.” A grade is given to students in each class, based on how much they improved from their original test score.

A common misconception during this year’s SLO test was that students had to show 50% improvement overall. Students acknowledge that trying on the pretest makes doing well on the graded post-test much harder. Senior Dennis Kravchenko said, “What if you get a 90% the first time, and a 91% the second time? You still did amazing on the test, but there’s no gain from it.”

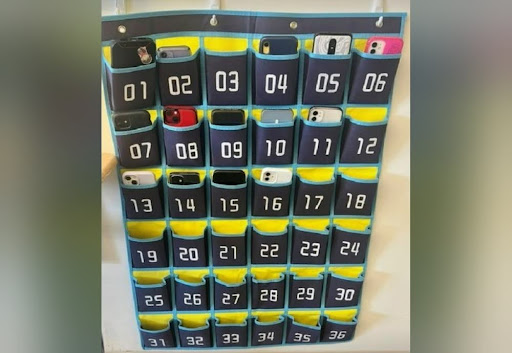

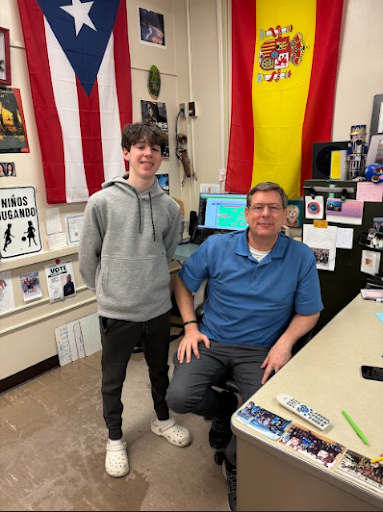

This led many students to attempt to manipulate the tests. Eric Frei –Mayfield’s Assistant Principal for Student Affairs in Grades 9-10- said, “ A lot of that [scoring] is kind of technical-information that only the teacher would know. When you start sharing that, that’s where students start to manipulate.”

Frei did not believe that informing the students on how the SLO tests function as a system would reduce the abuse of the system.

When asked about how students viewed the importance of the SLO tests, Kravchenko said, “I alternated, five A’s, five B’s, five C’s, five D’s. I don’t think I looked into any of the problems on there.”

According to Frei, the SLO testing system is built around the idea that students will do their best on both the pretest and the post-test, in order to display improvement accurately. When students begin to cheat this system, they skew the results-and not necessarily in their favor. The problem with guessing or purposely failing is that it gives no indication a student’s actual capabilities.

“I’ve seen people submit empty scantrons, with one answer filled in,” senior Aastha Dhakal said. Apparently, some students have no problem cheating the SLO system.

However, the ability of teachers will also be assessed by the improvement of the students they teach, according to the state legislation that mandates SLO testing. This means that the actions of the students impact their teachers, either for good or bad.

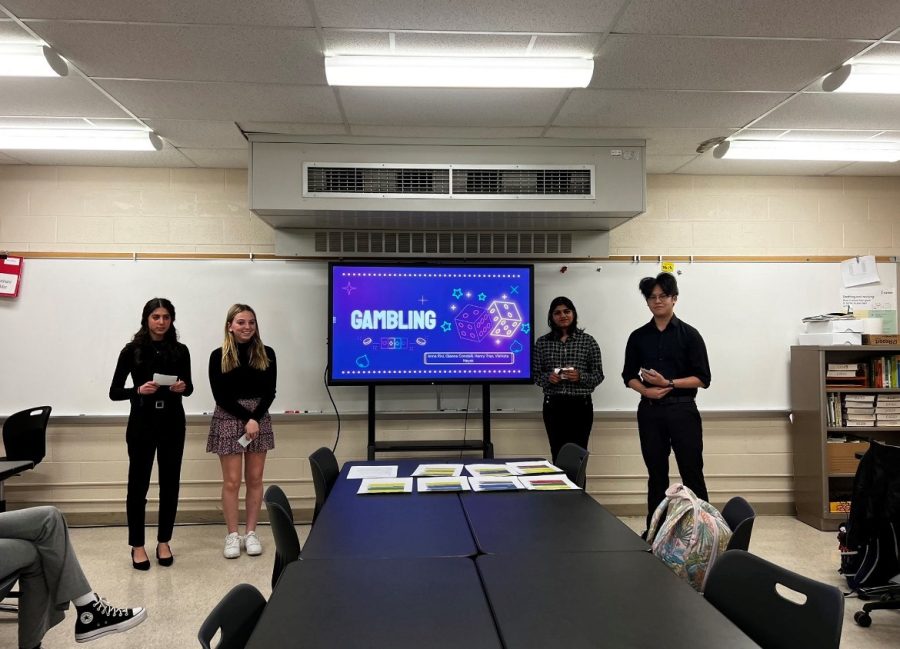

The implications of the SLO system are twofold. Frei and Loncar maintain that if used correctly, SLO testing has the potential to provide teachers and school districts with the information they need to modify courses to fit student needs. For instance, if a calculus class already excelled in trigonometry functions, but were weak in inverse derivatives, the course could be adapted to focus more on the weaknesses.

However, if used incorrectly, the system becomes relatively useless. If enough students disregarded the initial test, the data from the SLO tests wouldn’t have any technical meaning, because it was all guesswork.

This year is the first year of SLO testing, and Frei said “At the end of the [SLO] process, we’ll have to come back and reevaluate if the way we did it was successful.”

The general conclusion of the student body at Mayfield is that SLO testing will only work if everyone tries their best on both tests –a belief that has the support of the staff, as well.