Racially degrading mascots stir controversy

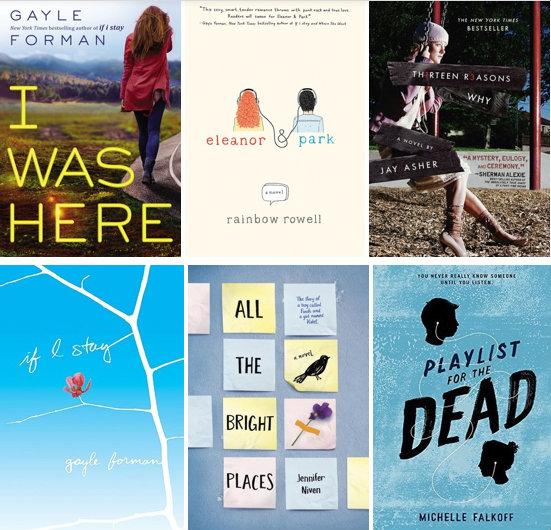

Out with the old, in with the new; the Chief Wahoo logo, shown left, and the Block C cap serving as the predecessor. Photo by Joe DeNardo

April 26, 2015

Native American mascots for professional sports teams, such as the Cleveland Indians “Chief Wahoo” or the Washington Redskins, are detrimental and set us back as a society.

I never chose Chief Wahoo. He was slapped on my head as a kid and I thought nothing of it. It became a rite of passage—sporting the Chief on your cap or jersey was a time-honored tradition in Cleveland spanning close to a half century.

But the time has come for the Cleveland Indians to sever the ties between their offensive mascot and focus on the one thing fans of the Tribe want them to do: Win baseball games.

Since 1915, Cleveland’s professional baseball team has been known as the Indians—and since 1947, a toothy-grinned cartoon, Native American has donned the caps of legendary players such as Bob Feller and Satchel Paige.

The original Wahoo lasted from 1947-1950 and was even more degrading than the one we’re familiar with today—complete with a hooking nose and mustard yellow complexion with a ponytail. In the 1951 season, the team switched to the Red Wahoo the city has become hastily engaged to ever since.

Controversy ensues over the logo when diehard Tribe fans, clinging to the last threads of the iconic 1990s teams, clash with the opinions of Native Americans, who don’t appreciate being seen as caricatures and insist that their children “are people, not mascots.”

Indians President Mark Shapiro and CEO Paul Dolan see an apparent solution in Cleveland’s “Block C” logo, which came to fruition in 2009 after the Tribe took Wahoo of the road batting helmets. The Block C, which many fans think is “boring” and “generic”, has been worn on opening day for the last few years while Wahoo beams off the left sleeve of their uniforms.

However, rather than embrace and accept the changes in a changing world, over 70% of Cleveland fans still hold Chief Wahoo close to their heart, according to multiple surveys taken by the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

“Many fans don’t see it [as offensive],” wrote the Editorial board of the Cleveland Plain Dealer “They view Wahoo through the lens of their youth, when they learned to embrace Wahoo the way they did Bugs Bunny, as loveable and funny, and before they knew anything about racial stereotypes.”

This is where striving for change runs into a buzz saw. Since Chief Wahoo is a cartoon, the really stubborn fans are blinded by a screen of ignorance and feel that the world hasn’t gone through any changes since Chief Wahoo’s return in 1980.

It is possible for there to be common ground in the argument, and it all starts with the fans being considerate to those Native Americans who have an honorable cultural standard to uphold.

Andrew Johnson is the executive director of the American Indian Center in Chicago and a Cherokee Indian who also appreciates what the city’s professional hockey team, the Blackhawks, did to discourage the idea of Native Americans being perceived as Cartoon Savages.

“If you went to a Hawks game 20 years ago, you would see all the costumes and comical stuff. You really don’t see too much of that today,” Johnson told NBC News. “The Blackhawks have made an overt effort not to televise them. They try to discourage it.”

While the Blackhawks make a hard-hitting decision to remain as professional as possible, the Indians organization has done no such thing—often allowing full headdresses and painted red faces to be put on the jumbotron inside the stadium.

It is not impossible to free ourselves from the constricting bind these degrading mascots have on our culture. The Atlanta Braves made the long awaited change from the wickedly offensive “Chief Noc-a-Homa” in 1986 with the help of many concerned fans.

It takes a cohesive effort—as fans we are responsible to say when the time has come for us to take the next step. The fallout of this struggle is on the horizon, so why not do it sooner rather than later? It’s time for us to move forward, not only as a city, but as a society.