Supported-housing companies have no right to fail

May 24, 2019

The vibration of his ringing phone distracts the man from current work. He reaches into his pocket, retracts his device, and peeks at the showing number. Recognizing it as the company that oversees the care of his schizophrenic brother, who lives, alone, the man answers it.

He opens his mouth to utter a greeting, but is interrupted by a monotone voice, “I’m sorry, sir. Your brother was found dead this morning by the police.”

The main problem of such supported housing programs for institutionalized mental patients is not whether they can live by themselves, but rather the lack of management from the overseeing companies.

In the state of New York, residential facilities (adult homes) are provided for patients diagnosed with mental illness in order to take them out of a hospital setting. However, through an investigation in 2002 pursued by “The New York Times”, investigators found these homes to be centers of neglect and abuse toward their patients.

As a result, in 2014, the court of New York issued an order to allow 4000 patients residing in these harsh homes to leave and enter a new program known as supported housing. In these programs, individuals are given the chance to live and take care of themselves in apartments funded by the state. Patients learn to work, pay bills, cook, and overall, live a normal life within designated communities.

However, some supported housing programs are not as efficent as they may seem.

A recent episode aired on Frontline featured issues of these supported housing programs. In ‘Right to Fail’, journalist Joaquin Sapien tracked down various examples of institutionalized patients who suffered throughout the program.

One man, Nestor Bunch, diagnosed with schizophrenia, experienced multiple failing outcomes within the program.

In just a participation span of five years, Bunch found his first and second roommate dead, occupied various poorly constructed apartments with no hot water or heat, and landed in the hospital with serious injuries after allegedly being assaulted in the streets. Bunch also had a history of suicidal tendencies and was said to require more help in supported housing.

The Institute for Community Living, the company responsible for care and documentation of these patients, made no effort to configure his situation and merely continued to place him in one horrible living space after another. The CEO of the company also made no acknowledgement that he was almost beaten to death.

All Bunch wanted was a normal and independent life.

Bunch’s deceased roommate, Bernard Walker, also had been poorly and inhumanely treated throughout his time in the program.

Records obtained by Sapien and Walker’s family from the Federation of Organizations showed that he was inconsistent in taking his medication on his own and requested extra help. The documents also stated that the federation sent a staff member per his request, but instead of looking for him when they found him not at home, they left and never returned.

This was two days before Walker’s death.

In addition to the lack of accountability and oversight, companies involved in the investigation of Walker’s death such as the Department of Health and the Office of Mental Health refused to release the results under the claim that it was a violation to Walker’s privacy. Not only is his death report unknown to his family, but these companies are able to hide the true nature of their care behind privacy laws.

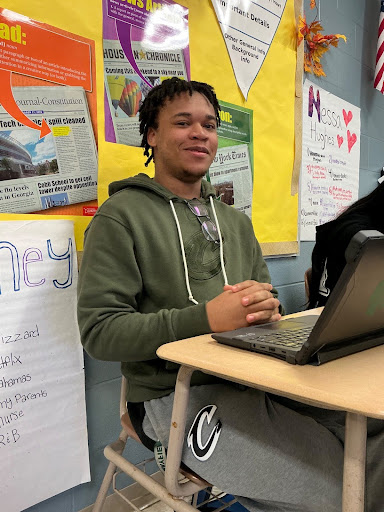

Sophomore Ilona Grazi also watched the Frontline episode and was outraged by Walker’s death. She said, “I think the thing that made me most angry was the fact that [Bernard Walker] had died and the companies really didn’t do anything to prevent it. It’s not fair that a person died because the staff weren’t doing their jobs.”

The last man investigated was Abraham Clementy, a 69 year old also diagnosed with schizophrenia. Clementy’s living state was horrendous. Sapien found him living in a filthy apartment infested with insects, trash, and sometimes animal feces. Clementy also had an untreated infection on his finger, obviously indicating he had not been seen by any medical professional in some time.

Not one person at the ICL made an effort to move or help Clementy.

Clementy’s records from his previous adult home showed that he was not in good shape to live on his own. Officials still moved him into the supported housing program.

After various altercations, Clementy moved back into his previous adult home.

Clementy spoke to Sapien again and thanked him for his help, as he believed he was much happier back with supervised care. He said, “I don’t wanna be on my own again.”

Grazi believes the program would better improve if the companies took into consideration the wellbeing of their participants.

“Honestly, just the workers doing a better job of making sure the [patients] are okay. I also think that they should make sure everyone is ready to be on their own before throwing them out into the real world,”said Grazi.

Proper care needs to be provided for all individuals diagnosed with mental illness. It is not right to simply abandon them and watch as they continuously fail over and over again without any effort for change being made.