Teachers, students admit struggle with Zoom learning

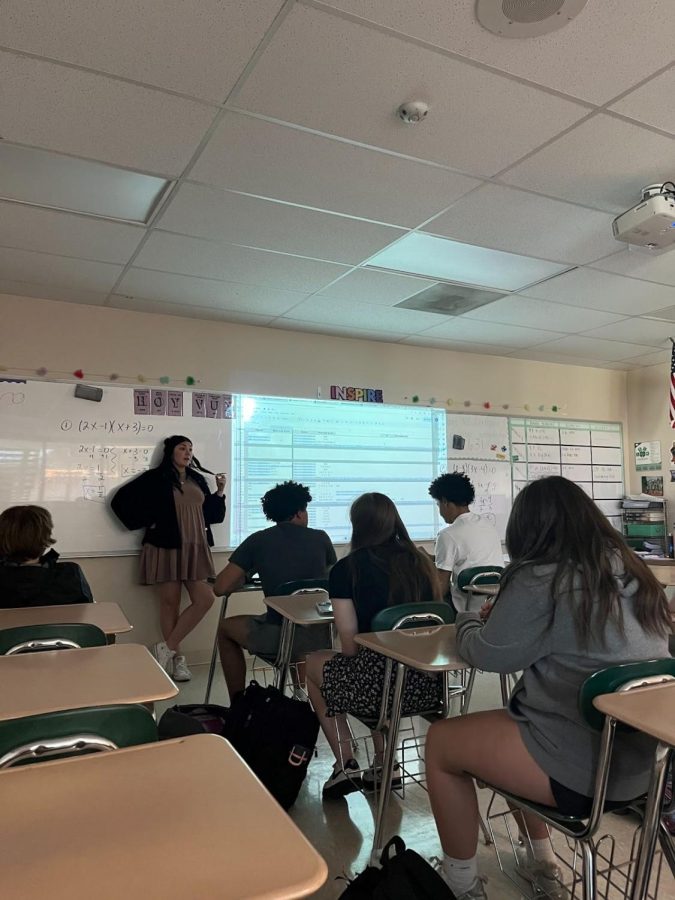

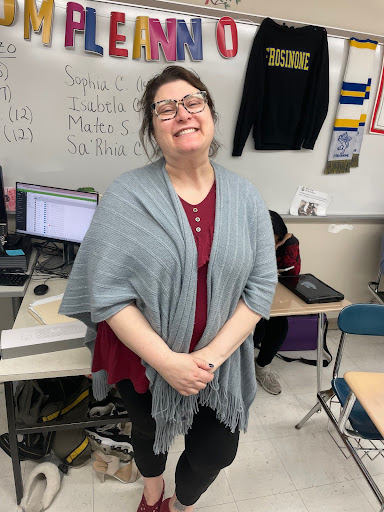

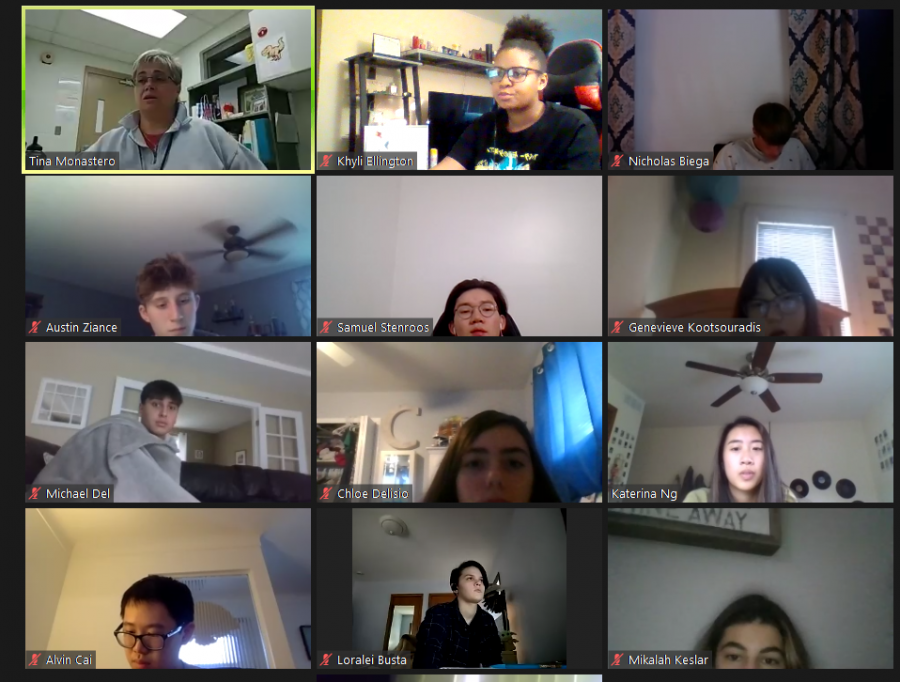

Health teacher Tina Monastero delivers instruction to her students in a Zoom meeting.

December 3, 2020

360 minutes.

That’s how long remote learners and teachers are asked to stare at a screen each day for instruction. According to Mayfield students and teachers, Zoom instruction hasn’t been easy.

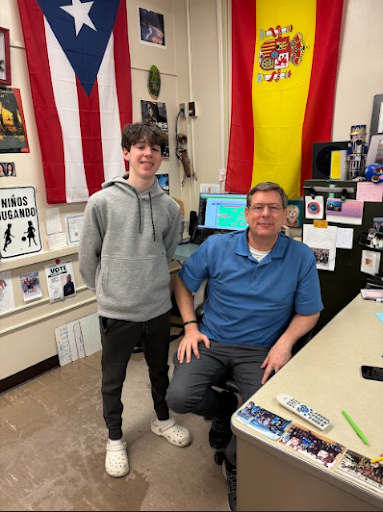

Spanish teacher Phillip Deaton admits he isn’t a fan of teaching his classes via Zoom because of the lack of human interaction. “I really got to know the students [in previous years] and that interaction is what makes teaching worth it. I know you can ask them questions via Zoom during classes, but in my experience, those answers were short and they were quick to hit the mute button once again,” Deaton said.

Abby Ferritto of the English department also acknowledges that a Zoom connection isn’t the same as a personal connection in class. “One of my favorite parts about teaching is getting to know my students, and the format of online learning doesn’t leave a lot of time and space for separate conversations,” Ferritto said.

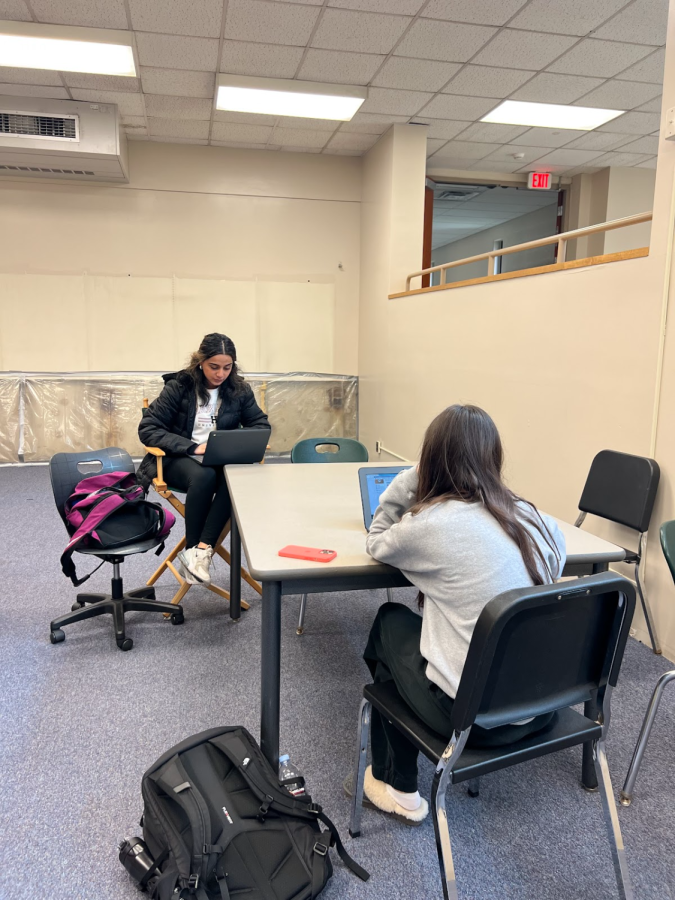

Student participation is dwindling and asking questions via Zoom has become a slight issue for some virtual students, according to sophomore Isabelle Coppersmith. “I am much better at explaining myself in person than over zoom, and issues with the internet connection make it hard to understand,” Coppersmith said.

Coppersmith believes there have been drastic changes working on Zoom. Coppersmith said, “People [on Zoom] are less likely to speak out and ask questions (myself included), so it makes some of the instructions unclear.”

According to Deaton, it’s also easier to teach in-person because it’s a little more difficult to incorporate virtual learners. Deaton said, “Many times [remote learners] chat with me when they have a question, but I’m not in front of the camera so I don’t see it. Therefore, it has been a struggle getting virtual students to voice their questions so that I know they have one and can return to the computer and answer it.”

Ferritto indicates that along with the struggle to teach with a face mask, another struggle is how difficult it is for her to connect with virtual students who are less eager to answer questions. “Reading and lecturing with a face mask become very uncomfortable,” Ferrito said.

When given the choice of going in-person or working virtually, many might assume that students would return to school, but Coppersmith doesn’t think it’s that easy. “I and my mom both have asthma and my mom has scarring in her lungs from when she was a child and this puts us at moderate to a low high-risk rate if I or my sister got [Covid-19],” she said.

Ferritto reveals when teaching remotely, everything must be packaged and ready to share at all times. Ferritto said, “This can be a challenge because it means that you can’t just write an important concept or idea that you’ve just come up with on the board for students to internalize.”

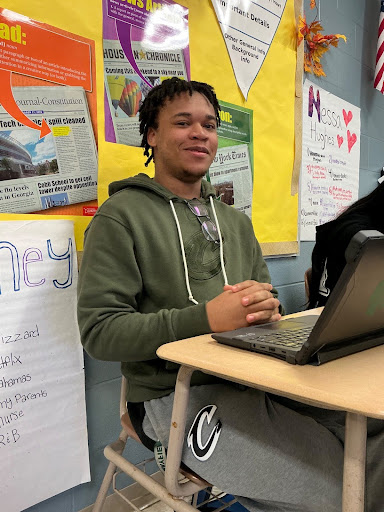

When it comes to reviewing for assessment, Deaton admits that doing review games isn’t as hands-on as he’d like. Deaton said, “With seeing the students for fewer days during the week, I’ve had to focus on the grammar principles in class to make sure and solidify those which take away from the vocab review. We did a lot more group style games before like using buzzers, fly swatter, Pictionary, group whiteboard races, etc.”

Deaton finds it frustrating to teach a world language via Zoom because it takes more time to ask questions. Deaton said, “As a teacher, you have to ask the question, call on someone, wait for them to unmute his/her microphone, ask you to repeat (many times), and then wait for them to give you the answer. This process goes a lot faster in person.”